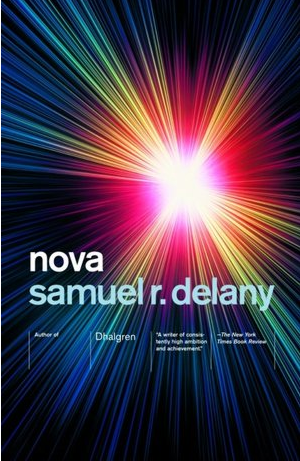

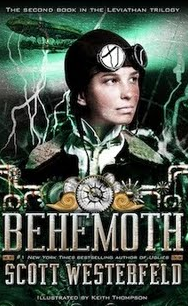

I just finished reading two great books. nova, by samuel r. delany, is a science fiction classic; and I predict that Behemoth, the second book in the Leviathan Trilogy, by Scott Westerfeld

I just finished reading two great books. nova, by samuel r. delany, is a science fiction classic; and I predict that Behemoth, the second book in the Leviathan Trilogy, by Scott Westerfeld, will become a fantasy classic.

World building is crucial in science fiction and fantasy. Both genres take place in strange worlds with totally alien landscapes, codes of ethics, and/or creatures. These worlds must ring true from the start, because the sooner the reader gets her balance and bearings, or at least finds promising and intriguing handholds, the more likely she is to keep reading. But science fiction and fantasy have slightly different rules for world building. The worlds in science fiction must be based, at least tentatively, on accepted scientific theory and fact. Fantasy has no such constraints, but it does demand that its worlds be true to their own rules and history. Actions must be predictable and understandable. If one character can levitate and all the others can’t, the author must provide a good reason for the discrepancy.

levitate and all the others can’t, the author must provide a good reason for the discrepancy.

Both delany and Westerfeld are master world builders. The settings of their books are totally strange, intensely fascinating and completely believable. The reader slips into them as if she’d been there before. And this, I have come to discover, is one of the secrets to successful world building. The writer must assume that the reader has already been there. Of course both the reader and the writer know this isn’t true, but it must be done, because the story is usually told from the point of view of one or more main characters who have been there before. In fact, they probably live there. Even if the story begins with the point of view character landing in an alien environment, the author should still be writing as if the reader already knows what is there. He should assume that the reader knows that, for instance, the sky is a lovely shade of apricot and the water is red, and concentrate on telling her how the character feels about this and how he reacts to it. This not only informs the reader that the sky is apricot and the water is red, but also gives her important information about the character. Every writer knows he should show, not tell, but this is subtly different. If the author is able to “convince” the reader at some subconscious level that she knows all about this strange world, the reader says, “Oh, I guess I do, but I seem to have forgotten, but these hints he’s giving me should help me remember.” And then she does what every enthralled reader does—she begins to imagine. And with her imagination, the author’s world comes alive.

The first chapter of nova begins with:

“Hey Mouse! Play us something,” one of the mechanics called from the bar.

“Didn’t get signed on no ship yet?” chided the other. “Your spinal socket’ll rust up. Come on, give us a number.”

Mouse begins to respond, but a blind, insane spacer lunges into the room with a tale about being a cyborg stud for Captain Lorque von Ray. They were flying into a nova to mine its Illyrion and he looked into its brilliance and was blinded.

delany writes all this as if the reader already knows who Mouse is, what instrument he plays, what a spinal socket is, what a cyborg stud is, where the bar is, what Illyrion is, why a ship’s captain would fly into a nova to get it, and who Captain Lorq von Ray is. The reader has to, or it would shatter his illusion, because this part of the tale is told from Mouse’s point of view and he already knows all this stuff. And so the reader obligingly begins snapping up clues and filling in the blanks, and by the end of chapter two, she has the answers to all the above, is comfortable in delany’s world, and has even more questions that need answering.

The first chapter of Behemoth begins with Alek giving Deryn a fencing lesson. They are snarking at each other, giving the reader clues about their personalities. The next thing she notices is that the author refers to Deryn to as “she”, but Alek seems to think she is a he and the reader’s interest sharpens. Then Westerfeld reminds her that the fencing lesson is taking place on the topside of an airship that has just left the Italian peninsula and is now over the Mediterranean, and there are rumors of two German ironclad warships in the vicinity. Deryn calls Alek a Clanker, the German enemy. Ah-ha, the reader says, so this is could be World War I. It couldn’t be World War II because airships were outmoded by then. But what is a girl doing on an Allied airship with a German, and why are the Germans called Clankers? And what is a hydrogen sniffer? A Huxley ascender? Where is the airship going? The reader’s mind goes into overdrive trying to “remember” the answers to these questions, and by page two, she is hooked. From this beginning Westerfeld leads the reader into the alternate reality of a World War I fought by Clankers

(the German machine culture) and Darwinists (Allied forces who fight with genetically modified animals); and he does it with the coy precision of a strip tease artist—one enticing tidbit of information at a time.

But why bother with these intricate other worlds? In other words, why bother with science fiction and fantasy. The easy, cop out answer is that fantastic realities are fun and interesting, but this isn’t why these two genres have such avidly loyal fans. The real reason is that once the author has got the reader to truly believe in his world and to care about its people and politics, he is free to point out the world’s problems (which usually bear a remarkably close resemblance to our own) and perhaps actually solve them. He can say why this policy or that idea failed and he can kill off the oh so familiar bad guys. None of this is quite so simple in realistic fiction and can come across as moralistic or pedantic.

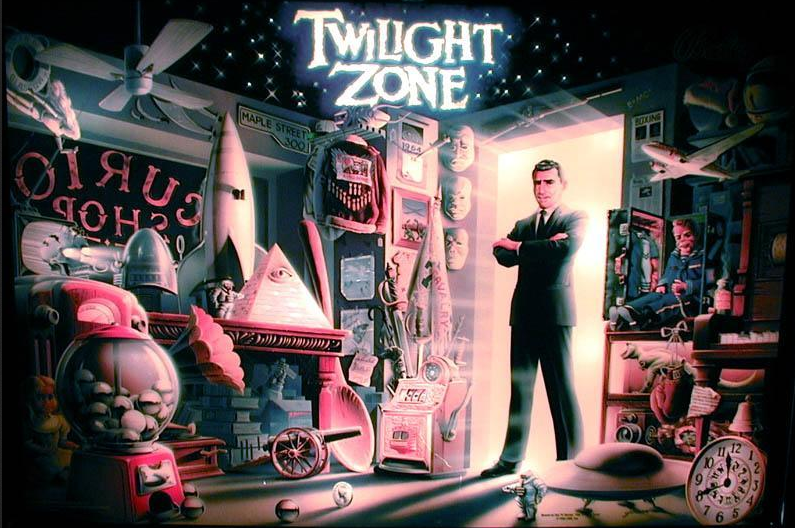

Rod Serling wrote screenplays full of scathing comments about war and US post WWII society. He was the angry young man of Hollywood, constantly fighting with censors—until he got his own show and began writing a blend of science fiction/fantasy stories called The Twilight Zone. The censors left him alone, he could say whatever he wanted because his stories weren’t about real life. However, anyone who has seen even a few of The Twilight Zone shows can’t help but feel their sharp, political humanist edge.

Science fiction and fantasy can step into places where realism fears to tread. And they succeed because they take place in a whole new world.

One thought on “A Whole New World”

Hi, Chrissy! I’ve nominated your blog for an Inspiring Blog Award. You can see and copy the rules here: http://isiopolis.wordpress.com/2012/08/18/inspiring-blog-nomination-for-isiopolis/

You inspiring us all to keep on writing!